Kati in her Burnsville, Minnesota studio. She also has a studio in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, where she spends part of the winter.

Kati in her Burnsville, Minnesota studio. She also has a studio in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, where she spends part of the winter.by Elizabeth Grams

Kati Ritchie (Servant Branch) has spent most of her life looking attentively at the world, and then helping other people to see what she sees. Hundreds of Trinity School at River Ridge alumni know her as a masterful art teacher who taught them new ways of seeing. She’s still at it, but nowadays she’s looking at the world of the new creation and, through her icons, laboring to help other people see resurrected life.

Kati has worked as an archeologist, translator and photojournalist. She encountered the charismatic renewal on a reporting assignment in 1971 and soon joined the group that formed Servants of the Lord community. In 1987 she left graduate studies in art to answer the call to teach at the new Trinity School in the Twin Cities, where she established the art program and became the stuff of legend. (Her students remember her weeping at the beauty of a curved line and demanding that they identify reds, blues and yellows in a clove of garlic.) As an artist, she has produced hundreds of paintings and drawings, more than 100 Polish paper cuttings and now more than 100 icons.

In 2001, when Kati’s allergies and the symptoms of multiple sclerosis brought on the need for a new job, she went to Joel Kibler (Servant Branch) to ask his advice about what to do next. “Would it give you joy to make icons?,” he asked. Kati realized in a flash that it would, and she’s been learning how to create them ever since.

The tradition of iconography dates back to the third and fourth centuries. An icon is an image that owes its distinctive style to a unique use of light and perspective. Icons always contain the golden-haloed figures of one or more saints, angels or the Lord himself.

“An icon is not meant to be a photograph,” Kati explains. “It’s a window into heaven, a vision of a spiritual truth, the uncreated light of Christ shining through a transfigured body. It’s visible proof of the incarnation, God dwelling among us, his people.” She also calls it “an embodied prayer.”

Icon painters are said to “write” an icon rather than paint it because they do not view their work as art, but as a pictographic form of Christian teaching similar to a sermon.

Over the last 12 years, Kati has traveled across the US and to eastern Europe and Russia in order to study icons and learn from other iconographers. She found a mentor in world-renowned master iconographer Ksenia Pokrovsky. Ksenia, a native of Russia who now lives in Massachusetts, taught herself iconography in the 1960s when iconography was banned in Russia. Kati has made several extended visits to Ksenia’s home and workshop in Massachusetts to continue to study her craft.

The language of traditional iconography takes years to learn and master, even for a trained artist like Kati. Anytime she sets out to paint, Kati always begins with research. “I look at a lot of pictures of similar icons—examining them as an archeologist does,” Kati explains. (She once worked as a field archeologist in Mexico and in Israel.) Kati looks past the variations she finds in traditional sources and tries to identify the essential form or prototype of the figure. She then copies stroke for stroke what earlier iconographers did so she can figure out how they did it. (She has a highly trained hand due to her graduate studies in the atelier method of fine art.) Only then is she ready to ask herself, “What can I do to make this more accessible and still keep the form?”

Using an egg tempera paint that she mixes herself, Kati begins creating an icon by measuring and drawing the outlines of the figure or figures, then painting the background. Next she paints the bodies of her subjects, and completes the faces and hands last. As she paints, Kati continues to consult traditional icons and she works prayerfully throughout the process.

“For me,” Kati says, “I have to get more serious when I’m working on the figure. If there’s a conflict in my life I have to resolve it to keep on working. If I can’t pray, I can’t paint!”

From the start, Kati’s interest in icons went hand in hand with her desire for ecumenism. In the centuries after the 11th-century split between Eastern and Western churches, iconography flourished primarily in the East. Icons became and have remained a central part of worship for Orthodox Christians. But a modern renaissance in iconography has spread to Catholic and Protestant churches as well. Ksenia, herself a member of the Russian Orthodox Church, has played a significant role in this movement. In all her years of teaching, she never refused a student for reasons of denomination.

Ksenia’s student and fellow teacher Marek Czernecki shares Kati’s hope that their work in iconography will build unity among Christian churches. “One of the reasons I love iconography,” he says, “is that I see so much ecumenical potential in it. It’s a job, occupation, vocation and ministry, so it’s important to know what you’re doing! I think that’s what’s important about Kati and her work: she’s part of a larger process of ecumenism. Kati and I are part of the same process, and so are thousands of other people of all denominations. It’s a collective effort, and a lot of it is the work of the Holy Spirit.”

Kati has received commissions from a variety of churches and individuals, including a dual-rite parish in Denver which holds both Roman and Byzantine liturgies. For her latest project, one of her largest, she painted four six-foot icons for Pope John Paul II Catholic Church in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, where Kati spends her winters. It took her over a year. This April, the local Catholic bishop presided over a ceremony for the installation of the four icons.

The pastor of the church, Fr. Don Malin, explains that his reason for asking Kati to make the icons was to honor the church’s namesake, Pope John Paul II, who came from eastern Europe and worked for ecumenical outreach to the Eastern churches. In that same spirit, Fr. Malin invited the Methodist and Episcopal pastors in town to attend the installation ceremony. “We’re very happy with the icons,” he says.

Kati sees more hope for ecumenism in the use of icons in Western as well as Eastern churches: “Icons can provide a window into the kingdom where we all will be transfigured like Christ and united with him.”

***

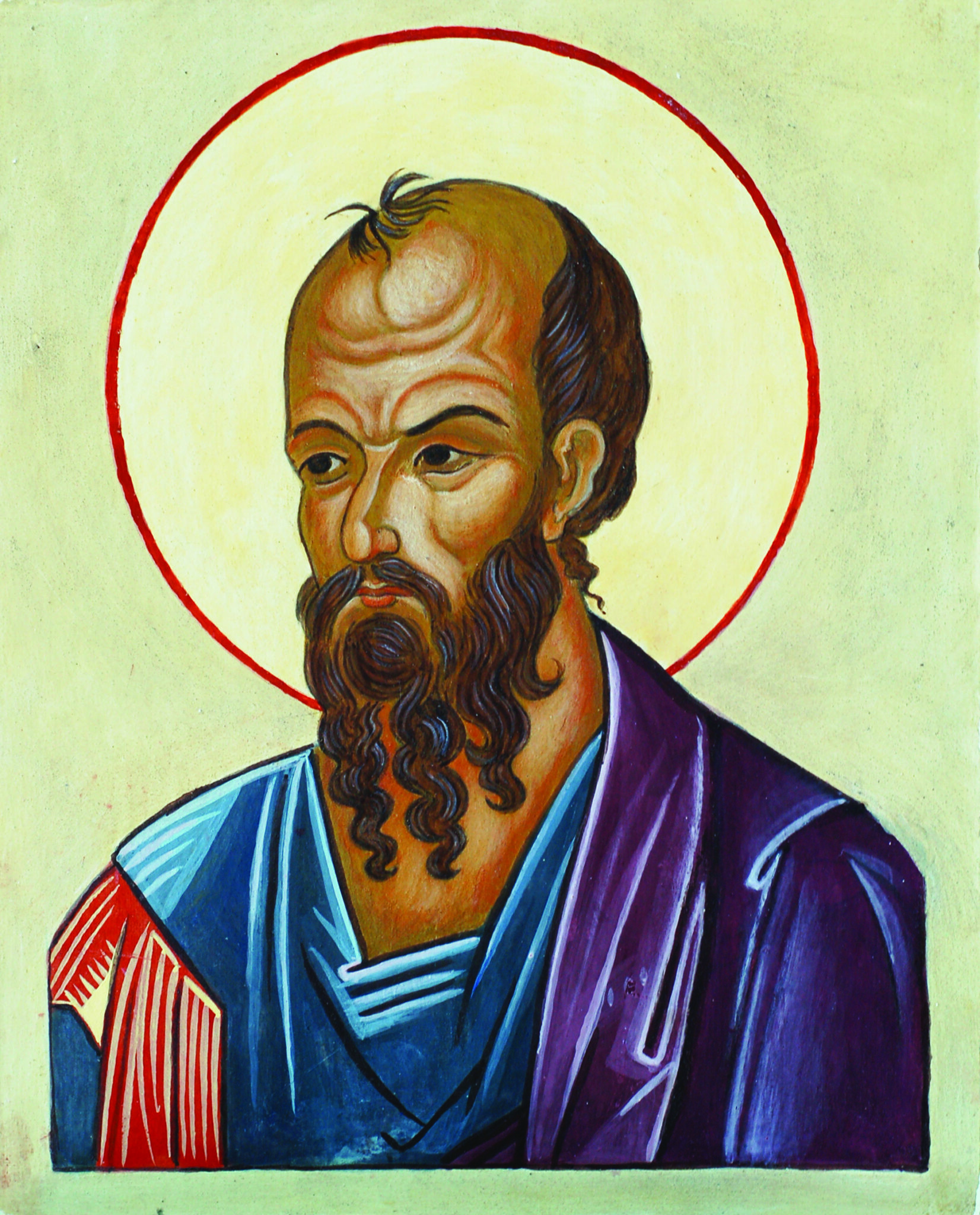

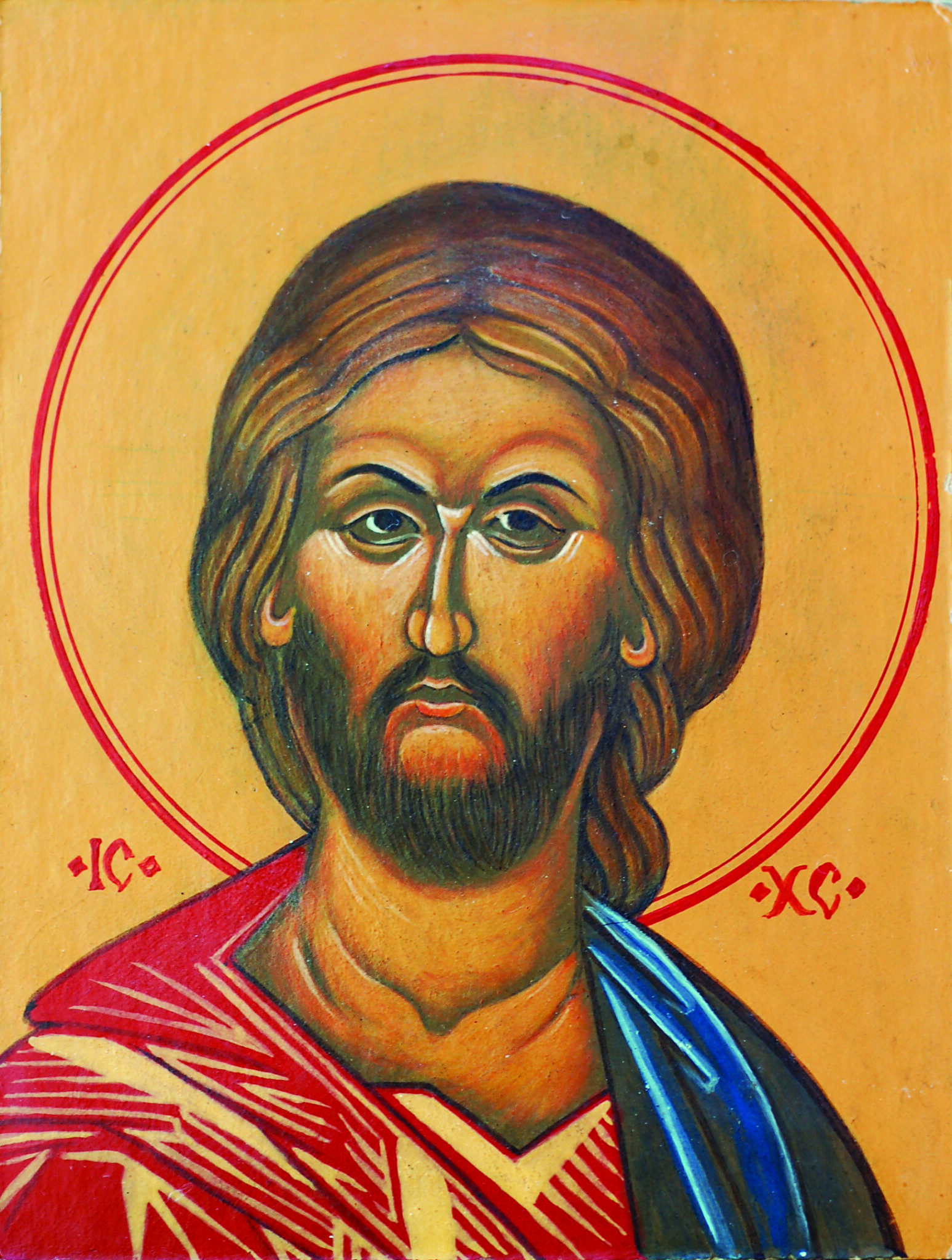

Below are several examples of Kati’s work. Usually she paints with the traditional medium of egg tempera (egg yolks mixed with ground natural pigments and vinegar).

Since the figures are always either holy men and women or angels, the uncreated light of Christ’s transfiguration illuminates them. This light comes from within them, shining out through their eyes and casting no shadows. The perspective is also a heavenly one. To our eyes, trained in realism, the figures seem somewhat distorted. This is due to the use of inverse perspective: the figures are painted as though seen from heaven, from the side of the figure opposite the viewer. As Kati says, “An icon is not meant to be a photograph. It is a vision of a spiritual truth.”

Kati’s icons bear obvious resemblance to the earliest images of Peter and Paul from the fourth century. They show Peter with the same short, curly white hair and beard, and Paul with a long brown beard and balding head. It is possible that these features bear some resemblance to the two men as their Christian brothers and sisters knew them, but in any case these features have become part of traditional representations of each one.

The four icons pictured below are a set recently installed at Pope John Paul II Catholic Church in Pagosa Springs, Colorado. They are painted with acrylics on canvas.

In the sanctuary of the church, these four six- foot icons hang under a crucifix. In addition to the names added to the portraits, clues from the visual language of iconography help to identify the figures for the viewer.

In Eastern traditions, the Archangel Michael usually carries a rod, since he leads the heavenly armies in battle against the devil, an an orb, since he protects the entire earth. Here he holds a sword instead of a rod of authority; the sword became more traditional in Western art over time.

Mary and John traditionally stand at the foot of the cross, Mary on Jesus’ right and John on his left. Here Mary’s heart is depicted—a specifically Western tradition. The small stars on Mary’s garments symbolize the indwelling of the Trinity. “She’s wearing red shoes,” Kati says, “because [in iconography] . . . she always wears red shoes.”

John is always beardless to signify his youth.

“The icon of Pope John Paul II was chosen because he is the patron of the parish,” Kati explains. “It’s not a physical portrait of him. I first painted a portrait from photographs of him as a younger man, and some of my old Polish friends who had known him approved the portrait. Then I stylized the portrait. He carries the keys of Peter and wears his red traveling cape, white cassock, papal cape and cross.”

Kati’s icons have a clean and simple appearance. She strives for “the simplest way to convey truth.”

Jesus is always shown wearing a red robe with a golden band on one arm and a blue outer garment. The red symbolizes his humanity, the blue his divinity, the gold his kingship. Kati painted this icon on a small piece of cardboard that now hangs in her car to remind her of the Lord. (She refers to this icon by the name “driving Jesus.”)

Kati offers this advice, once given to her, for someone new to icons: just sit quietly in front of one and let Jesus love you.

Responses

Susan Clifford says:

July 17th, 2025 at 10:30 PM

Dear Kati, The attunement and diligence of your artwork bear witness to your love and devotion to your Faith.

My deepest condolences to your family for the leaving of your adorable brother, Tommy. I always remember him as cheerful with a ready smile and bemused.

I wish I could get together with you sometime in Minneapolis. Sincerely with love and admiration. Susan Clifford