Kelly Park has been completely rebuilt through the efforts of neighborhood children and adults and will be formally dedicated this summer.

Kelly Park has been completely rebuilt through the efforts of neighborhood children and adults and will be formally dedicated this summer.by Elizabeth Grams

Photos: Margaret Anderson; courtesy of Beth Sanford

For Lu Ella Webster, a lifelong resident of South Bend’s northeast neighborhood, Kelly Park is a place of happy memories. She can recall playing with other children, black and white together, on the domed monkey bars and pump merry-go-round back in the 1950s when the park was new. But in more recent years, she says, the park became run-down. Some neighbors would warn children not to play there. There were hypodermic needles on the ground, and cars speeding close to the remaining playground equipment made it dangerous for little ones. The park’s one bench had broken slats. Its swingset and basketball hoops were faded and worn.

Today the park has been rebuilt from the ground up, with two basketball half-courts, a pavilion, a perimeter fence, new playground equipment and dozens of beautiful trees. This summer, South Bend city representatives will gather with neighbors and friends to cut the ribbon across the park’s brand new entrance and officially dedicate it.

The seeds of the park’s resurrection lay in the dreams of a group of neighborhood children. With the help of many others moved by those dreams, Beth Sanford (South Bend) and her friend and neighbor Lu Ella turned them into a reality. They raised $220,000 in donations and pushed the reconstruction forward from start to finish.

Matt and Beth Sanford and their children live half a block away from Kelly Park. They’ve watched their neighborhood change in recent years as new houses were built, attracting families connected with the University of Notre Dame, located just to the north. Wealthier households moved in next to or replaced middle or lower-income families. Kelly Park remained uninviting and unsafe, until some neighborhood children voiced a desire to change it.

These eight-to-twelve-year-olds from the nearby Robinson Community Learning Center initiated the renovation of Kelly Park and raised the first $6,000 in grant money.

These eight-to-twelve-year-olds from the nearby Robinson Community Learning Center initiated the renovation of Kelly Park and raised the first $6,000 in grant money.The children were attending a program at Robinson Community Learning Center, a Notre Dame-sponsored outreach to the neighborhood. After taking a closer look at their neighborhood through the program, they told their leader, Lu Ella, that if they could improve one thing about their neighborhood it would be Kelly Park. In 2013, the group of a dozen eight-to-twelve-year-olds made a small grant proposal for park renovations that was approved.

Lu Ella still lives on the property where she was born and raised, directly across the street from Kelly Park. She says her family—she’s one of 15 children—were the first African-Americans to move into the neighborhood. She has been a leader in neighborhood projects and helped the children develop and publicize their hopes for the park.

In 2013, Beth was a stay-at-home mother of five and also an architect by training. With her children in school, she was starting to feel a creative itch. She asked the Lord about it and decided she should offer to help Lu Ella. She had no idea that she had just gotten herself into a five-year project.

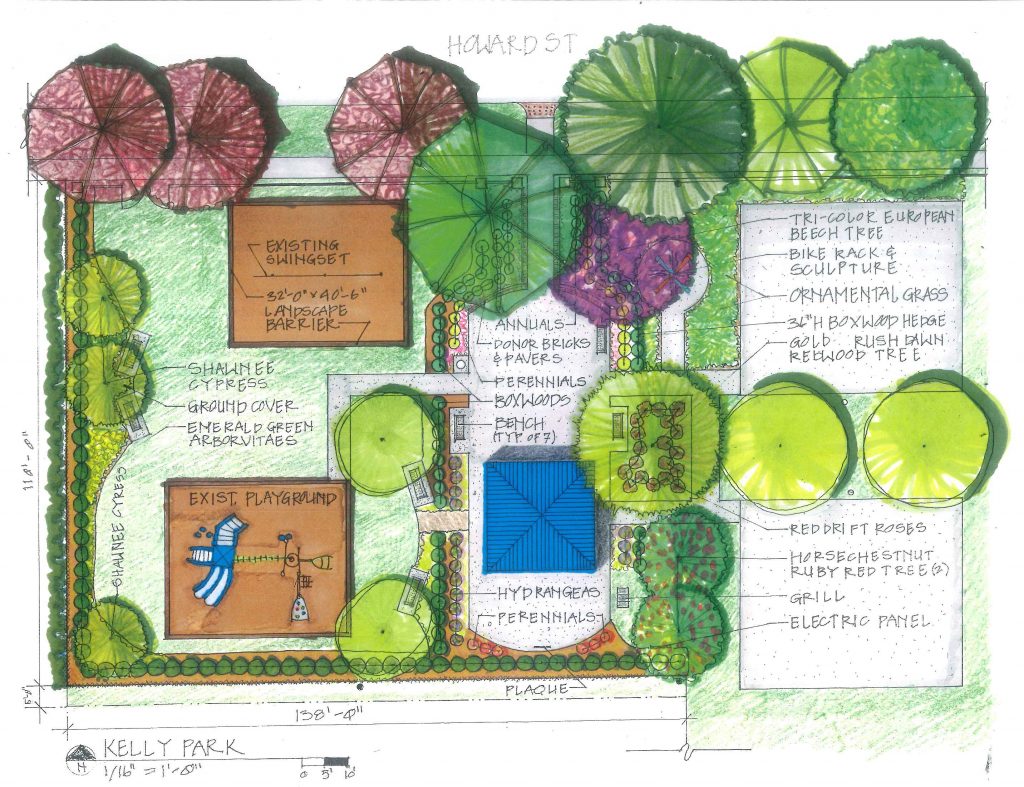

“The first thing we did was to have a design charrette with the kids,” Beth says. “We worked with them to draw pictures of what they wanted. They wanted a basketball court, a walking path for parents to exercise while their children play, a gated playground, a place that was handicapped-accessible. They wanted benches for adults and elderly people, a pavilion and grill. What they wanted was not just for themselves, but for the community. I was really inspired.”

Beth and Lu Ella and their team took the design proposals to the city’s parks department. “They told us, ‘That’s great! We don’t have any money.’ So we said, ‘Neither do we! Okay, we’ll raise it.’”

Beth and Lu Ella started pounding the pavement. They quickly secured a $10,000 donation from a neighborhood revitalization association. They approached their neighbors around the corner, the owners of a local business, who wrote out a check for $7,500 on the spot. Encouraged, they kept going, eventually securing tens of thousands of dollars towards the renovation.

Beth worked with vendors, cutting costs and asking for discounts on materials and labor. She found out that Indiana masonry workers had an apprenticeship program and asked if they could build the entrance piers for free. “I brought this really architecturally pretty drawing of the piers, and the guy in charge said, “That’s great, but I can’t build that”—because they’re just first-year apprentices. And I said, ‘Oh! Well, what can you build?’ So we sat and modified the drawing.”

She worked with neighborhood children and youth groups to help clean up trash in the park. She spoke with neighbors about what was going on in the park and asked for their input, and she and Lu Ella kept in touch with city officials. They made sure to express their thanks to everyone involved. “Lu Ella and I fed the masons a full meal, and they said, ‘Wow, we always just get cold pizza!’”

Beth had plenty to learn, since her background had been mainly in commercial, residential and light industrial architecture. “As an architect I’m a research junkie,” she says. “I started contacting my friends who are landscape architects to get their opinions. I called the manufacturers of the swingset: ‘this is how I’m interpreting your safety standards. Is this correct?’ I found out how expensive playground equipment is, about the requirements for loose-fill barriers, about surface materials and their compaction rates. Even things like where to put the grills and trash cans—you have to think about it from the city’s maintenance standpoint. I felt like it was God’s gift to me that I got to do this.”

Beth utilized all the volunteer manpower she could find, like these apprentice bricklayers, to help with the renovation.

Beth utilized all the volunteer manpower she could find, like these apprentice bricklayers, to help with the renovation.Beth’s son James saw kids playing on the new courts even before the paint was down. “The courts are definitely very well used. With two separate courts now, you can have a playful game with grade school kids and a real scrimmage with some high schoolers. I think that was really smart.”

At the Sanford house, family mealtime conversations often came back to the park. Matt works as a machinist in the Notre Dame Department of Physics shop which donated scrap metals to the local blacksmiths’ guild, where the men designed and built the new entrance sign for the park and a sculptural bike rack designed like a carousel. Matt himself engraved the plaques on each of the park benches with the names of donors. James brought fellow Trinity classmates out to help paint the new fencing. “Our family unit has grown in patience and support,” Matt says. “We pray for Beth’s work at the park and we’re proud. The Lord has guided her.”

After working together so long, Beth and Lu Ella call one another sisters, and their families have become close. “When something goes wrong, we text each other: ‘Remember the Lord is in it.’ Every step of the way, we said, ‘Lord, lead us to the people you want to lead us to, and to the people you want me to ask for money.’”

This year, workers planted 26 boxwoods and 116 trees, including 83 arborvitaes that created a green screen around two sides of the park. Recently Beth noticed that someone had been stealing some of the shrubs. As she was thinking about what to do, she saw a woman walk into the park with a wagon and some dirt, looking like she was about to take off with another shrub. Beth started to pray and got the sense that, instead of confronting the woman, she should listen to her. The woman began talking about how Notre Dame had paid for all the plants, and how she and some friends were going to come over and fertilize them. Beth explained to her that she and others had raised the money to renovate the park, showing her pictures of the renovation. While they were talking, a group of boys rode up on their bikes, and Beth invited them to help water the plants. Soon the woman was helping to clean up around the plants, and the boys started to help her. “God bless you,” the woman said to Beth. “You’re good with these boys.” She left promising to come back and help again.

“Beth and Lu have been great partners,” says John Martinez, Director of Facilities and Grounds for South Bend’s parks department, which honored the two women as volunteers of the year in spring, 2018. (They even got to throw out the first pitch for a South Bend Cubs minor league baseball game.) “This has been well-received by the whole neighborhood,” said John. “I wish we had more neighborhood groups like them.”

“It’s a good feeling,” Lu Ella says, seeing the fruit of their labors every day from her home. “One day there must have been a hundred kids over here in the park, and what a blessing to hear the laughter! And the Notre Dame law students had their family picnic over here. We had a man whose wife passed and they wanted to have a celebration for her, and all the family were saying let’s do it at Perley Park, and he said, ‘No, she grew up across the street. This is the park she played in.’ They had it here in the park. And then they did fireworks later on at night and it was beautiful.”

Now Beth sees neighborhood families, rich and poor alike, playing alongside one another in the new park. “For me, learning how to build a park is one thing, but now I can see the social impact, and I know how God has had his hand in it . . . you have all the expensive new homes coming in next to all the older homes that have middle to lower-income families. Before, the new families would not even come to this park. Now you’re starting to see the neighborhood coming together. It’s like a place of union.”