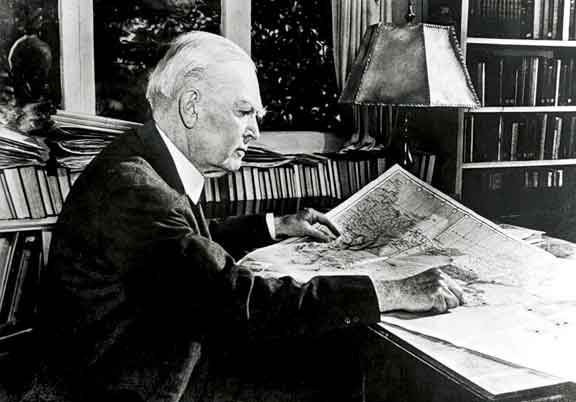

John R. Mott, a Methodist layman and pioneer of the ecumenical movement, helped organize the World Missionary Conference and spread its informal motto, "the evangelization of the world in this generation."

John R. Mott, a Methodist layman and pioneer of the ecumenical movement, helped organize the World Missionary Conference and spread its informal motto, "the evangelization of the world in this generation."Commentary

By Sean Connolly

At a February conference in Rome, Catholic Cardinal Walter Kasper made a bold proposal to Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist and Reformed leaders: “an ecumenical catechism,” a joint commentary on the Apostles Creed, the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer.

That was unthinkable 100 years ago, when a group of Protestants met in Edinburgh, Scotland, for a conference credited with launching the ecumenical movement. The president of the conference read a telegram to the delegates from Anglican leaders containing a single, prescient Scripture verse: John 17:21.

Nowadays, every place the word “ecumenism” goes, John 17:21 follows: scrappy local prayer services, papal encyclicals, harangues over the scandal of a divided Christianity. It’s ecumenism’s ubiquitous theme—Jesus’ prayer to his Father—usually shortened slightly: “that they may all be one . . . so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

A simple logic governs today’s ecumenical movement: unity comes first. Before “the world may believe,” before Christians can achieve the final clause of John 17:21, we must fulfill the first clause, unity. This translates into lots of high-level dialogues aimed at resolving doctrinal disagreements, but not into much common evangelistic effort.

But there’s another way to read John 17:21—in reverse.

It’s startling to look back from today’s dialogue-heavy ecumenism to discover that the 1910 conference didn’t involve a lick of dialogue.

That meeting—the World Missionary Conference—aimed in a different direction. Organizers like Methodist layman John R. Mott saw great promise for spreading the gospel through the expanding network of railroads. They adopted a motto, “the evangelization of the world in this generation,” and let nothing stand in their way. They invited Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Quakers and others to get together and talk, banning dialogue about doctrine, so they wouldn’t be diverted from conversation about missionary cooperation.

Simple logic. In the words of one Baptist newspaper, “The world has to be evangelized. God wills it.”

The logic produced intriguing possibilities, like cooperating in some foreign mission fields, rather than working in parallel along denominational lines. After all, as delegate Cheng Jingyi put it, “Denominationalism has never interested the Chinese mind. He finds no delight in it, but sometimes he suffers for it!”

Tragically, four years later, this boatload of missionary zeal struck a big rock—World War I. The energy devoted to sending missionaries got diverted into a fight for Europe.

But the boat survived, and soon the same churches began talking about unity. Orthodox Christians joined a conversation in 1920 that eventually yielded the World Council of Churches in 1948. At the Second Vatican Council in 1964, the Roman Catholic Church made an irrevocable commitment to ecumenism.

This thread of discussion about unity leads straight to Cardinal Kasper’s proposed catechism, a joint articulation of the basics, relevant to any future missionary cooperation.

But many veterans are concerned for the ecumenical movement’s future. Ecumenical dialogue “is perhaps in danger of becoming a matter for specialists and thus of moving away from the grassroots,” Cardinal Kasper says.

Anyone who has counted nearly as many churches as people in a small town could agree with Anglican Archbishop N.T. Wright’s remark: “Let’s not fool ourselves that if we can agree around the table in Rome, this solves all problems of church unity. . . . It’s just the beginning.”

2010 is as ripe with evangelistic possibilities as 1910. The Internet and the global economy are a railway for ideas and people such as the world has never seen. It’s time for all who love ecumenism to pick up the flag of the World Missionary Conference—“the evangelization of the world in this generation”—to seize on opportunities created by fruitful dialogues and bring the ecumenical movement back to the grassroots.

The story of the last 100 years shows Christian unity coming as the direct result of missionary cooperation, not the other way around. John 17:21 is still the right verse—but read it in reverse: By banding together to help the whole world believe, Christians from every denomination might just fulfill our Lord’s great prayer, “that they may all be one.”

Bold missionary action launched the ecumenical movement. The same can see it through to 2110.

Responses

sjconnolly says:

March 20th, 2010 at 11:15 AM

Basil D. from New Orleans sent in this note and gave permission to put it here:

"It is interesting that in your article you cite the Edinburgh Conference of 1910.

One of the delegates at that conference was my great grandfather's younger brother, the Anglican Bishop V. S. Azariah. At that conference this Indian bishop praised the sacrifices made by the English missionaries, but maintained that what was most important was the relationship of love that grew between the English and the Indian churches:

“ Through all the ages to come the Indian Church will rise up in gratitude to attest the heroism and self denying labors of the missionary body. You have given your goods to feed the poor. You have given your bodies to be burned. We ask for love. Give us friends.” Bishop Azariah, Edinburgh 1910.

I think in the missionary outreach of the People of Praise the stress is really on love and friendship. My great grand uncle would certainly be proud of us.

Basil"