by Sean Connolly

Photos: Craig Lent

NOW IT WAS THE DAY OF PREPARATION for the Passover; and it was about noon” (Jn. 19:14).

“On the first day of Unleavened Bread, when the Passover lamb is sacrificed, his disciples said to him, “Where do you want us to go and make the preparations for you to eat the Passover?” (Mk. 14:12).

If you read the four Gospels and pay attention to the sequence of events during the week of Jesus’ crucifixion, you may spot a puzzle. Matthew, Mark and Luke all indicate that the Last Supper was a Passover meal, but John says that Jesus was crucified the day before the Passover. Who’s right?

Colin Humphreys, a physicist and a metallurgist at the University of Cambridge, tackles this puzzle in his book The Mystery of the Last Supper (2011). Humphreys is versatile, relying on astronomy, computer programming, knowledge of ancient calendars, biblical insight and deduction. His book is a fast read, a bit like a detective story. His conclusions are perhaps surprising, but they do have an advantage—they appear to solve the mystery.

HUMPHREYS BEGINS BY PINPOINTING the date of Jesus’ death, including the day, month and year. The day is easy, since all four Gospels indicate that Jesus died on a Friday. The month is easy, too, since Passover always occurs on the 15th of the month of Nisan in the Jewish calendar.

This means that, according to John, Jesus died on the eve of Passover, Nisan 14. But if the synoptic Gospels are correct, then Jesus died on the day of Passover itself, or Nisan 15. (Recall that Jewish days run from sunset to sunset, so the post-sunset Last Supper and the crucifixion could have happened on the same day.)

Getting the year right is harder. Humphreys narrows down the time frame to 10 years—AD 26 to 36, a range most scholars accept. To home in further, he turns to astronomy.

The Jews used a lunar calendar. Humphreys says, “The priests of the temple in Jerusalem had a team of men who, each month, looked for the new crescent moon. When at least two of these trustworthy witnesses agreed they had seen it . . . trumpets were blown to tell all Jerusalem that it was a new moon and a new month.”

THIS RAISES AN INTRIGUING POSSIBILITY. Since Jewish dates are determined by the moon, is it possible to wind the lunar clock backward and figure out when Nisan 14 or Nisan 15 would have occurred during the target timeframe?

Scientists have tried this since the 1930s, but there’s a problem with their efforts. The start of a Jewish month depended on seeing the crescent moon. There are observational factors such as the brightness of the crescent, the darkness of the sky, atmospheric degradation, etc., that could have affected when the Jews declared the start of a month.

In 1981 Humphreys worked with Oxford astrophysicist Graeme Waddington to see if they could include these observational factors in computer calculations. They published their results in the scientific journal Nature in 1983. Humphreys says, “These calculations agree with over one thousand recorded observations of new moons and give the correct answer every time. We can therefore have considerable confidence in them.”

Waddington’s calculations show that there are only four possible years between AD 26 and 36 when either Nisan 14 or Nisan 15 fell on a Friday: 27, 30, 33 and 34.

Humphreys is able to eliminate the years 27 and 34 by correlating data from the Gospels with data from Roman historians. He then rules out AD 30 since, as he argues, John the Baptist’s ministry could have started no later than AD 28, and Jesus’ ministry lasted for three years. This leaves only the year 33. By translating the Jewish calendar to the Gregorian calendar we use today, he comes up with the date Friday, April 3, AD 33!

Humphreys goes on to confirm this date using a different approach.

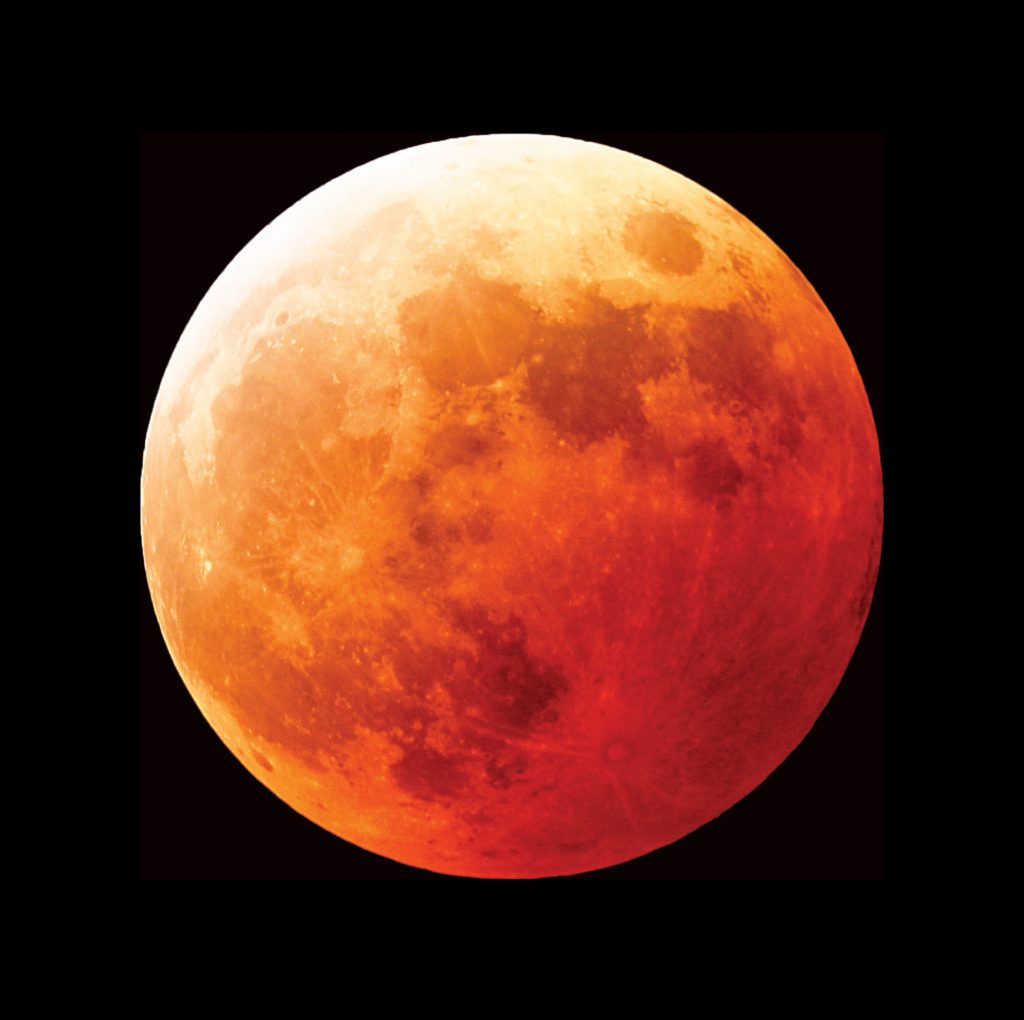

In Acts 2, Peter quotes the prophet Joel: “In the last days . . . the sun shall be turned to darkness and the moon to blood.”

Some scholars suggest that on the day of Pentecost Peter wasn’t predicting future events, but claiming that these signs had already taken place. F.F. Bruce writes, “[L]ittle more than seven weeks earlier, the people of Jerusalem had indeed seen the darkening of the sun, during the early afternoon of Good Friday; and later in that same afternoon the paschal full moon may well have risen blood red in the sky in consequence of that preternatural gloom.”

In the ancient world, the phrase “blood moon” was used to describe a type of lunar eclipse that occurs when the moon is in the earth’s shadow, causing the moon to appear a deep, bloodlike red. (Perhaps you noticed the “blood moon” that appeared in the sky around Passover time in 2014.) Humphreys asked Waddington to calculate all possible lunar eclipses visible from Jerusalem during the time of Passover in the years AD 26 to 36. Waddington returned one and only one date, Friday, April 3, AD 33!

THESE CONCLUSIONS ARE INTRIGUING, but Humphreys still has some explaining to do. If John is right that Jesus died on Nisan 14, why do Matthew, Mark and Luke say that Jesus ate a Passover meal before he died? Humphreys puts forward his major hypothesis: perhaps John was using a different calendar from the other Gospel writers.

In modern times, we’re accustomed to relying on just one standard calendar. Yet many Christians are aware that Orthodox Christians use the Julian calendar to calculate the dates for Christmas and Easter, while Western Christians follow the Gregorian calendar.

The official Jewish calendar in use during Jesus’ lifetime originated during the Babylonian exile (586 to 537 BC). The names of the Jewish months and the sunset-to-sunset day are both based on the Babylonian calendar. What calendar did the Jews use before the exile?

This is a difficult question to answer historically, but there is a clue in Exodus 12:1-2, when God tells Moses when the new year should start. Humphreys suggests that the Jews were already relying on the lunar calendar in use in Egypt, and that they shifted the start date forward in keeping with God’s command.

The Egyptian lunar calendar measured its days from sunrise to sunrise. This means the Jews would have had to change the way they dated their feasts when they adopted the Babylonian calendar during the exile. In the preexilic calendar, the Jews would have slaughtered the Passover lamb and eaten the Passover on the same day, Nisan 14. But a Babylonian calendar would have meant that when it came time to eat the meal, after sunset, the date would have changed to Nisan 15.

Naturally, a dating change of this magnitude would have caused some controversy, and Humphreys points to several Jewish writers who believed that the official Jewish calendar was wrong about when the major feasts should be celebrated.

Is there any evidence that a preexilic calendar was in use during the time of Jesus?

ENTER THE SAMARITANS, a group that, as many scholars believe, lived in Israel before the exile, a group which, even today, follows an ancient calendar, one they claim goes back to Moses.

The Samaritan calendar is a lunar calendar, but it calculates the start of months differently, beginning them at conjunction—when the earth, moon, and sun come into alignment. This is the exact same way the ancient Egyptians calculated the start of their months.

Humphreys says Samaritan and ancient Egyptian calendars would have been equivalent—except that the Samaritans start their year in the spring, just as God told Moses to do. If this assumption is true, it would suggest that the Samaritan calendar and the preexilic Jewish calendar would have been the same.

Humphreys goes on to argue that at least two other groups, the Essenes and the Zealots, probably followed the preexilic Jewish calendar. Was Jesus following such an alternative calendar?

Humpreys sees a clue hidden in Mark 14:12. Mark tells us that the Passover lamb was slaughtered on the first day of the feast of Unleavened Bread, which was the Passover. This is impossible according to the official Jewish calendar, because the lamb was slaughtered the day before Passover, on Nisan 14.

But if Jesus was celebrating the Passover on Nisan 14, and using a calendar with a sunrise to sunrise day, then Mark’s sentence makes sense. Humphreys suggests that Mark was cluing his readers in to the fact that Jesus was using the traditional, preexilic calendar.

Humphreys sees another hidden clue in the “man carrying a jar of water” who was to lead the disciples to the upper room (Lk. 22:10). Most Jewish men did not carry jars of water, but Essene men did. The man carrying water could have been an Essene living in the Essene quarter of Jerusalem, someone who was willing to allow the disciples to celebrate the Passover early, because he was following the traditional calendar.

The official calendar puts Nisan 14 on a Friday in the year 33, but what day would Nisan 14 have fallen on according to the preexilic calendar? Humphreys and Waddington again wind the clock backwards and come up with an answer: Wednesday. In fact, the Gospels never explicitly state that Jesus and his disciples ate the Last Supper on a Thursday.

There are certain advantages to this scenario. Scholars have often wondered how it was possible for Jesus to eat the Last Supper on Thursday night, pray in the Garden, get arrested, appear for questioning before Annas, appear before Caiphas and the Sanhedrin for a lengthy trial, appear before Pilate, appear before Herod, and again before Pilate, all by Friday morning, the day when he was crucified. (Mark puts the time at 9:00 a.m.) If that Last Supper happened on Wednesday, there would be sufficient time for all these events.

HUMPHREYS FINISHES HIS BOOK BY pointing out the symbolism in play if his conclusions are correct: “By using the preexilic calendar, Jesus held his Last Supper as a real Passover meal on the exact anniversary of the first Passover, described in the book of Exodus, thus identifying himself as a new Moses, instituting a new covenant and leading God’s people out of captivity. Jesus died at about 3 p.m. on Nisan 14 in the official Jewish calendar, at the time the Passover lambs were slain, thus becoming identified with the Passover sacrifice.”

What do other scholars make of Humphreys’s conclusions?

In a 2013 article, Helen K. Bond, a scholar at the University of Edinburgh, accepts the astronomical calculations of Humphreys and Waddington, but rejects the idea that Jesus had to die on either Nisan 14 or 15, and so she comes to a different, less precise conclusion.

Oxford Bible scholar Nicholas King predicts that New Testament scholars will “bridle restively at this book,” but he says that Humphreys has made a case convincing enough that it needs to be answered by Bible scholars. King accepts Humphreys’s conclusion that the Last Supper happened on a Wednesday, but he points out that Humphreys does not give anything more than circumstantial evidence for some of his other conclusions.

In his book Jesus and the Victory of God (1997), N.T. Wright suggests that the Last Supper was not a full Passover meal eaten with a lamb, but a highly symbolic “quasi-Passover.” He believes that Jesus and his disciples celebrated the Passover before the date on the official calendar, consistent with what Humphreys concludes.

Pope Benedict XVI surprised many in 2007 when he suggested in his homily on Holy Thursday that Jesus celebrated Passover “at least one day earlier” than Thursday. But he didn’t go as far as suggesting that Christians move their Holy Thursday celebrations ahead by one day. Will that ever happen? Only time will tell, but until the issue is resolved you can read Humphreys’s book and draw your own conclusion.

Responses

Steve Pable says:

March 29th, 2018 at 5:11 PM

Wow! Thanks for this read, Sean!

I especially appreciate taking the time to give a little bit of the response of Humphrey's peers. And it certainly is helpful in showing how so much of the drama of our Lord's Passion could have come about in this Holy Week.

May God help us to proclaim the Good News of Easter victory boldly and fruitfully!

Thomas A.D. Ramadhani says:

November 1st, 2018 at 12:23 AM

Wow! Great. Thank you so much, Sean!

I'm finishing up my book on Jesus' human body and crucifixion. After Scott Hahn's "The Fourth Cup" and Brant Pitre's "Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist," Humphrey's book is the next. (Actually, after reading your post here, I immediately got myself a copy on Kindle). What you explain here is really helpful.

May God bless you and your ministry.

Fr. Thomas A.D. Ramadhani, SJ

Murray Hamilton says:

November 22nd, 2018 at 12:51 PM

Thanks,

I really appreciate the article. Either there is an explanation to these things or there are errors in the accounts of the four gospels. Let us not pretend we know better than God....if there are things we don't understand, it is better to still trust God because we have an abundance of evidence that He is trustworthy!

Rosheeka A Johnson says:

March 22nd, 2019 at 4:03 PM

Passover happens THEN a prep day THEN the first day of unleavened bread. Passover is the 14th day, ULB is the 15th day. The DAY of Passover is used as a prep day for ULB. Passover is brought in in the evening prior to the calendar day of the 14. ie 13/14 The lambs are killed on the preparation day between the actual Passover and the start of ULB which starts the evening of the calendar day 14/ the calendar day of 15.

Shane henderson says:

April 19th, 2019 at 2:19 PM

Jesus was crucified at nine in the morning and died at twelve in the afternoon.it was on a wednesday. He was taken down off the cross before sunset , as it was the begining of the first day of unleavend bread a HIGH day sabbath.and not a seventh day SABBATH.he was placed in the tomb just before the sun set.its the first day of unleavend Sabbath And not the seventh day sabbath where the mistake is made.jesus was not crucified on a friday.Jesus gave the sign that he would be three days and three nights in the tomb.and its three complete days and nights not parts of as some argue. Wednesday at sunset two saturday at sunset is three days and three nights.you can not get three days and three nights in a friday crucifixion.

Eric Gatera says:

May 21st, 2019 at 7:28 AM

It seems that Dr. Brant Pitre, the author of 'Jesus and the Last Supper' has also dealt with the last supper in his monograph quite intensively. It was published after Humphrey's book. He returns back to the Friday crucifixion as the proper date. He has also a word or two to say about Humphrey theory. Here is a link: http://historicaljesusresearch.blogspot.com/2016/01/was-last-supper-on-wednesday-review-of.html

Mandi Hodges says:

January 27th, 2021 at 10:14 PM

While I agree with day being the 14th, I do not agree that it was a Friday. The days of the week were not named until after the Messiahs death and resurrection. It’s actually the Babylonian Talmud that teaches Saturday is the sabbath and it was the Sanhedrin(who deny the Messiah) that so many fall into the trap of following. The Roman Catholics say its Sunday. I don’t trust any religion. I do not agree that we should name the days of the week, when truly no one knows that for sure, since the suns shadow was moved 10 degrees, as scripture tells us. Following the Sanhedrin or the Romans names for the days of the week are not something I personally promote. I keep the Passover(Melchizedek Bread and Wine) 14 days after the Spring Solstice, since we can no longer use the moon. Per scripture, the sun tells us our day. I do believe it was a full moon that night, but before the shadow was moved 10 degrees. Following the moon back then, wouldn’t make your years come in 10 days to soon. I believe we are to remember from where we fell and listen to no one(trees)that are a mixture of good and evil. Here is the patience of the set apart saints: they guard ALL of the Fathers commandments and keep the testimony of the Messiah.